Restorative Justice in Rwanda

begin quoteDuring my time at the Kroc School, I had come to understand restorative justice, but I had never seen anything like this. Rwanda brought restorative justice to life.

The following blog post was contributed by Master of Science in Conflict Management and Resolution student Kay Wilson.

Before I traveled to Rwanda, I knew about as much about the country as every other person in the United States. I had seen the movie Hotel Rwanda in high school. I had some vague recollection of Don Cheadle yelling at diplomats on the phone. That was where my expertise ended. This limited frame of reference did nothing to prepare me for the incredible country I was about to visit. While visiting Rwanda, I learned that the history of violence there is only the beginning of the story. What is incredible is what happened after the 1994 genocide. In the face of insurmountable loss and suffering, Rwanda became one of the best examples of restorative justice in the world.

When we arrived in Rwanda, we spent our first few days learning about the history of the genocide. This involved a deeply moving trip to the Kigali Genocide Memorial. It was during this trip that I truly came to understand what had happened in 1994. In April of that year, the Rwandan government, led by the majority ethnic group, the Hutu, launched a genocidal campaign against the minority ethnic group, the Tutsi. This coordinated attack had been planned for years in advance. In the months leading up to the genocide, the international community had a good sense of the impending danger, yet they failed to act. After the genocide commenced, the international community still failed to intervene. An armed rebel group, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), fought the genocidal government to end the violence. The RPF is the dominant political party in Rwanda to this day.

When I was standing in Kigali, it seemed unfathomable to me that violence like that had happened just 25 years ago. Kigali is a beautiful, growing city. It has everything from karaoke to rooftop bars. How had this incredible place emerged after such immense tragedy?

The answer is restorative justice. During my time at the Kroc School, I had come to understand restorative justice, but I had never seen anything like this. Rwanda brought restorative justice to life. There were three distinct parts of Rwanda’s response to the 1994 genocide that left me in awe. Firstly, the new government’s immediate response to the genocide was to abolish the death penalty. After one million people died in 1994, the new government decided that the killing had to end. Abolishing the death penalty was a huge step towards responding to the violence with a restorative justice framework.

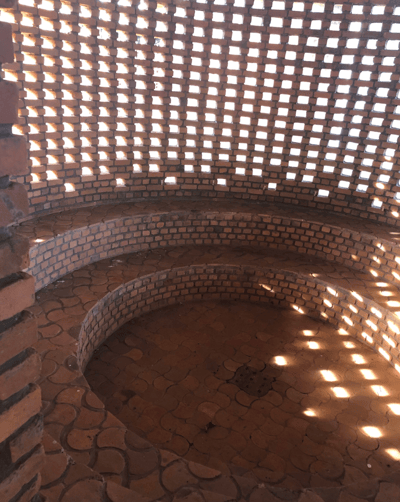

Gacaca courts were often held in circular, outdoor meeting spaces, like this.

The next piece of the puzzle was gacaca courts. Immediately after the genocide, Rwanda’s court system was dramatically overcapacity. It would take over 100 years for everyone in prison to be tried in the existing Rwandan court system. There was no way that this could deliver any type of acceptable justice. So the people of Rwanda looked back to more traditional forms of justice. By combining traditional practices with the present-day needs of the community, Rwandans created gacaca courts. Gacaca literally translates to grass. Gacaca courts were a type of justice reserved for lower-level offenders who were remorseful for the role they played in the genocide. During gacaca court, a community would come together to address the specific crimes of an individual. The offender would take responsibility for their actions and apologize. Then any victims or survivors would have an opportunity to ask questions or talk about the impact that this individual had on them. Then the community would work together to decide on a punishment for the individual. This incredible example of restorative justice allowed communities and individuals to heal.

Though gacaca courts are undoubtedly incredible, some groups in Rwanda took it a step farther. In some instances, where both parties agreed, the perpetrator and victim would come together to make a reconciliation village. The process was straightforward. First, a perpetrator and victim would meet to talk. After talking, they would work together, side by side, every day, to build a house. Then they would build another house across the street from that house. In the middle of both of the houses, they would build a well to share. The offender would move into one house and the victim would move into the other. They would be surrounded by a community of others working towards the same goal. Reconciliation villages are beyond what I thought was possible.

Even though I was familiar with restorative justice already, I had no idea what it could look like in practice until I went to Rwanda. This trip allowed me to learn so much about justice and forgiveness. Rwanda is one of the most vibrant and welcoming places I have ever been. It was a privilege to learn so much in such an awe-inspiring place.

Ready to advance on your journey as a changemaker? Learn more about the Kroc School's Master of Science in Conflict Management and Resolution.

Contact:

Justin Prugh

jprugh@sandiego.edu

(619) 260-7573

About the Author

The Joan B. Kroc School of Peace Studies (Kroc School) at the University of San Diego is the global hub for peacebuilding and social innovation. Founded in 2007, the Kroc School equips the next generation of innovative changemakers to shape more peaceful and just societies. We offer master's degrees in peace and justice, social innovation, humanitarian action, conflict management and resolution, and a dual degree in peace and law — programs that have attracted diverse and dynamic students from more than 50 countries. In addition to our graduate programs, the Kroc School is home to the Kroc Institute for Peace and Justice (Kroc IPJ). Founded in 2001, the Institute supports positive change beyond the classroom. Through groundbreaking research, experiential learning, and forward-thinking programs, the Kroc School and Kroc IPJ are shaping a future in which peaceful co-existence is the new normal.