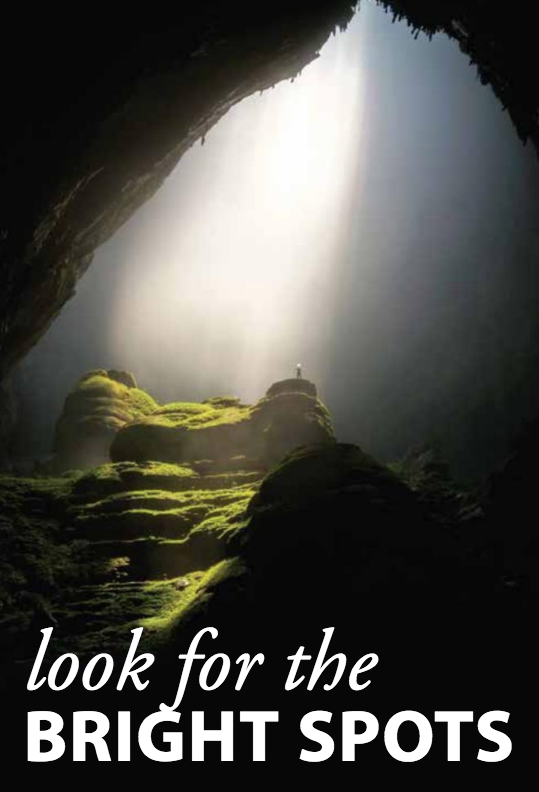

“Look for the Bright Spots”

Building Adaptive Capacity for (Predictably) Uncertain Times

Lately the opening line of the movie Love Actually has been running through my head a lot. The movie begins with Prime Minister David (played by Hugh Grant) ruminating about the state of the world after the September 11 terrorist attacks: “General opinion's starting to make out that we live in a world of hatred and greed, but I don't see that. It seems to me that love is everywhere. Often, it's not particularly dignified or newsworthy, but it's always there - fathers and sons, mothers and daughters, husbands and wives, boyfriends, girlfriends, old friends.”

I’m with “Prime Minister” Hugh Grant on this one. The state of the world is not as gloomy if you know where to look for bright spots where negotiation, diplomacy, and principled problem solving operates. The Kroc School was established to teach, practice and learn about the bright spots of non-violent, transformative social change that promote social justice. Conflict resolution is one pillar of this project. Its central praxis is conflict analysis, facilitated decision-making, and balancing power. After all, serious social conflict emerges in relationships where power and resources are skewed to benefit one party over another; it’s as true for family relations as for international relations.

It’s easy to focus on the ‘serious social conflict’ part. However if you can make ‘looking for bright spots’ a conscious lens, you will see that everywhere problems exist, there are people problem solving, figuring out how to make a positive difference. Let’s start with a story close to home. Two street gangs have carved opposing territories out of the neighborhood adjacent to the University of San Diego. They have claimed for themselves the two nicest resources: the public park, and the community recreation center. For the neighborhood kids, neither area is safe especially if you’re not the right color. This is a big problem! The problem solvers here are a small group of community members – a pastor, two local police officers, a high school administrator, and a local NGO – sitting around a table figuring out solutions. One solution often overlooked in cases like this is to orchestrate a conversation with the gang leaders, and bring them into the problem solving process – a strategy that has worked in neighborhoods and cities across the United States. Thanks to the diverse voices in that room, this idea is now on the table.

Let’s look at a problem that affects the whole planet. The United States recently pulled out of the Paris Climate accord, the best effort to date to tackle climate change and an extraordinary feat of negotiation at the highest level of human governance. The problem solvers here are the 343 mayors, 61 cities (including our 10 largest), and 3 states that have themselves adopted the historic agreement. Megacities around the world have emerged as major players in global policy realms - especially US cities because they have greater power over their budgets, assets, and because mayors have greater autonomy here than in most other countries. 12 US cities belong to the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group, which connects 90 cities worldwide, represents over 650 million people and one quarter of the global economy.

I recently returned from a trip to the Kurdish Region of Iraq where many Syrians and Iraqis displaced by ISIS have fled for sanctuary. The cities of the KRI have coordinated a humanitarian response that is unprecedented in the history of this region – particularly because a severe economic crisis hit the KRI at the same time that refugees started pouring in. “But you have to look for the bright spots,” one resident told me. “For every horrible act by ISIS, you will see 100 people helping to make things better.” She was right. Everywhere I looked, I saw people doing their best to welcome and tend to the vulnerable, and to lay the groundwork for reconciliation once ISIS has been militarily defeated. Sometimes these efforts weren’t “particularly dignified or newsworthy” but they represented familiar values: peacefulness, acceptance, diversity, equality, and democratic governance.

These values underpin the field of conflict resolution. The journey of human civilizations along the arc of history tells a good story – we are doing better than ever before at living together peacefully, at governing in ways that respect and protect diverse people and ideas, and institutionalizing equality before the law within democratic political systems. Yet until this story is a globally shared reality, we are all at risk. This is why the Kroc School has always sought a deliberate, holistic and symmetrical balance between conflict resolution, human rights advocacy, and progressive development policies. We take seriously the chant heard around the world during social change movements: “No peace without justice”.

Like other complex systems, society can only withstand so much inequality in relations before it undergoes a major transformation. The current milieu represents just such a series of challenges to “the way things are”. To my mind, this is a good thing. However our goal should be to strengthen the best of ourselves and our societies in the face of these disruptions. The first step is to look for the bright spots where people are connecting themselves and their resources to solve a problem – and then see what we each can do to enhance the learning, adaptation, and self-organization that resilience requires. That is conflict resolution at its best.

About the Author

The Joan B. Kroc School of Peace Studies (Kroc School) at the University of San Diego is the global hub for peacebuilding and social innovation. Founded in 2007, the Kroc School equips the next generation of innovative changemakers to shape more peaceful and just societies. We offer master's degrees in peace and justice, social innovation, humanitarian action, conflict management and resolution, and a dual degree in peace and law — programs that have attracted diverse and dynamic students from more than 50 countries. In addition to our graduate programs, the Kroc School is home to the Kroc Institute for Peace and Justice (Kroc IPJ). Founded in 2001, the Institute supports positive change beyond the classroom. Through groundbreaking research, experiential learning, and forward-thinking programs, the Kroc School and Kroc IPJ are shaping a future in which peaceful co-existence is the new normal.