Kroc School Alum Julie Ethan '13 (MA) on How to Build Bridges in Politically Opposite Relationships

Kroc School Alum Julie Ethan '13 (MA) on How to Build Bridges in Politically Opposite Relationships

The Kroc School connects regularly with its alumni, who are changemakers making bold social change locally and internationally. During a time in which politics are front and center in our minds heading into an election in November, we sought out the perspective of MA in Peace and Justice alumna Julie Ethan ‘13. She recently wrote a book that seeks to help people build friendships despite their political differences (more on this below). Please enjoy the following excerpts from our conversation with Julie.

What inspired you to pursue a Master's in Peace and Justice from the Kroc School?

I love a good story; a classic hero’s journey where the call to adventure is resisted. Then, with the help of a mentor, the hero enters a special world where she faces conflict, and a dark night of the soul, only to return to the ordinary world with the elixir of her conquests. In his book, Let Your Life Speak, Parker J Palmer was my mentor as he asked the question, “Is the life you are living, the life that wants to live inside of you?” My journey to answer that question placed me at the threshold of a very special world at the Kroc School. I moved across the country from Minnesota, with my spouse and middle-school aged daughter, to study peace and justice in 2012.

In my admissions essay, I quoted Dante Alighieri: “Midway upon our journey…The straightforward path had been lost.” Even in my decision to attend the Kroc School, my path wasn’t clear. At midlife, I was stymied about making a career transition. Learning about human rights, economic development and conflict resolution became a beloved part of that transition.

The political divide weighed heavily on me as I began my studies, and I remember Professor Topher McDougal saying that our country was an experiment, and the results were not in. I had grown up with the notion, as most of us do, that everything around me was the norm; the structures, the attitudes and the transactions were universal in my frame of reference. His statement challenged my framework. Studying global conflicts began to tell a different story than the one I knew.

Prior to becoming a graduate student, I asked: How could they? How could they dehumanize the outgroup and turn on them in violence? And now, I find myself asking: How could we? And—how can we? Especially as we watch the white racial narrative in our country unravel, and the upcoming election cause us to fear the previously unthinkable—civil war.

What are 1-3 lessons you learned during the Kroc School that have stuck with you?

One of the things that piqued my interest in the Kroc School were its cross-border programming such as the Transborder Institute (TBI). As a student, I was overjoyed when given the opportunity to complete an independent study at TBI under Professor David Shirk. I joined Vivien Francis, a former staff member, in accomplishing a grant project aimed at connecting high school students, through photography, to the undocumented migrant issues in the community of Escondido. Using the Ricigliano model of conflict mapping I’d learned in Professor Ami Carpenter’s class, I unearthed city council meeting minutes and police records, and held interviews with community members in Escondido to map the anti-immigrant policies initiated on the local level. Grievances between people groups—in this case, the middle-class residents versus the migrant community—were exacerbated by the partisan gridlock at the national level for enacting comprehensive immigration reform. In the vacuum of such reforms, local and state governing bodies were left to invent and experiment with policies; many detrimental to the migrant community.

Later, when I had the opportunity to research organized crime violence in Acapulco, Mexico as part of my capstone, I discovered the resilience that can occur in the vacuum of governance. In a country saturated by the influence and impact of non-state actors, the Catholic Church found itself in the position of first-responder during a six-month period of open warfare between cartel members and gangs on the streets of Acapulco. In the aftermath, it was everyday citizens who gathered together and sought assistance in learning about the roots of conflict as it applied to rebuilding peace in their community where, for too long, the shadow economy had been allowed to operate unopposed.

How have you been applying the skills, knowledge, and experience you gained since graduating from the Kroc School?

After graduation, I found myself back in Minnesota with politics on my mind. I began to develop workshops with a partner to teach campaign messaging. Our work was based on the research of former Berkeley professor, George Lakoff, a linguist and neuroscientist. We traveled to each congressional district in our state teaching how to create a holistically-framed message using shared values. Later, I joined Braver Angels as a volunteer workshop facilitator and chapter co-founder to bring conservatives and liberals together in highly structured discussions. The objectives included depolarization, and learning how to communicate across the partisan divide with friends and family in a non-threatening manner.

Are there any specific peace and justice projects you've been working on lately?

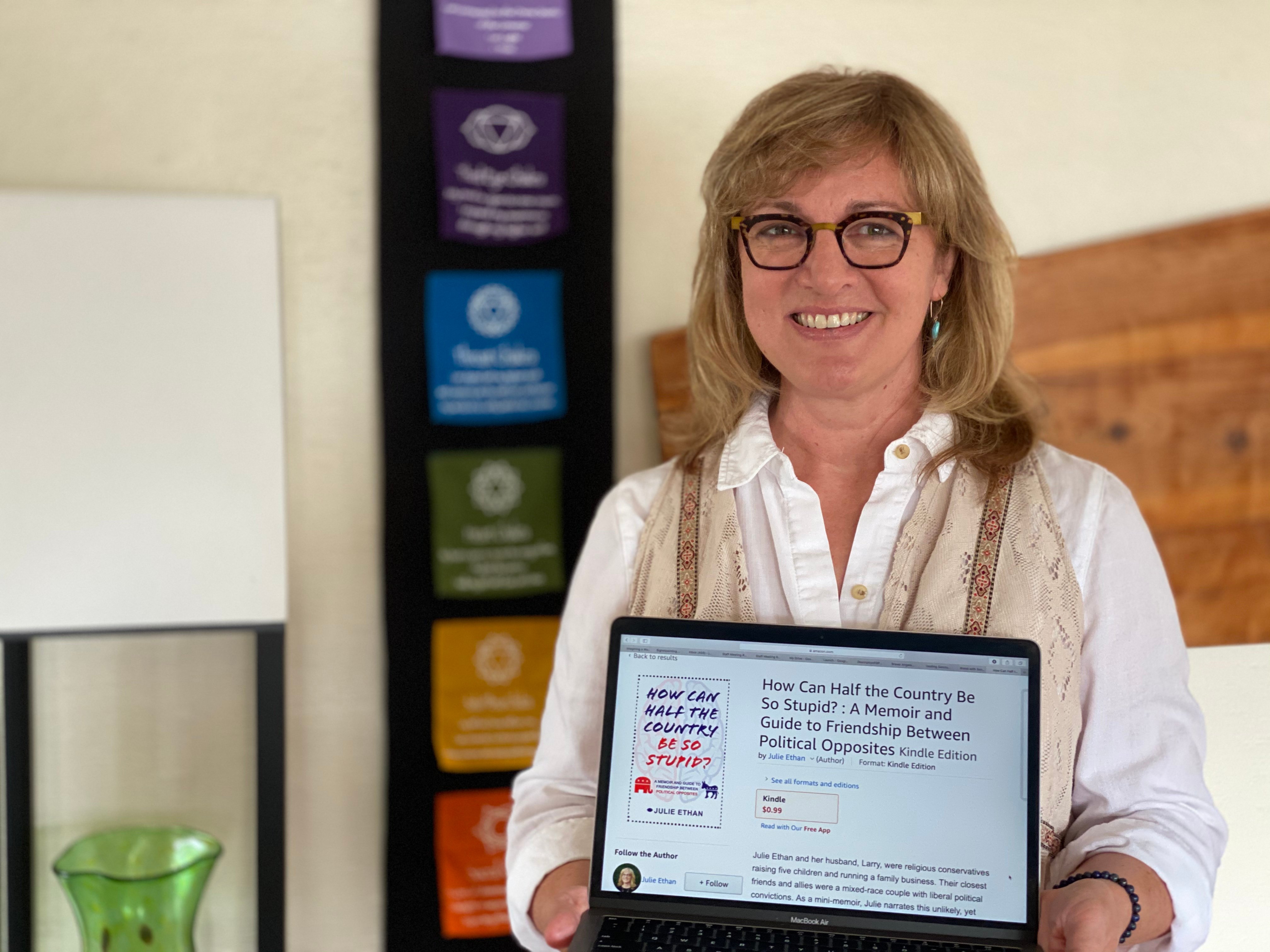

After my youngest daughter graduated from high school, we sold our home and moved back to San Diego in 2019. I spent nine months with a peace training organization that took groups to Tijuana to learn about immigration and border issues. I was laid off due to Covid. This gave me the opportunity to reflect, once again, on the Red/Blue divide. I completed a mini-memoir based on my lifelong friendship with my political opposite. The story serves as a backdrop to guide the reader toward depolarization and better understanding of how to manage their politically opposite relationships.

As a peacemaker, I struggled with the title of the book. In a quick poll of FaceBook friends, I asked—which title would compel you to pick up this book? The results were 3 to 1 in favor of: How Can Half the Country Be So Stupid? I decided to let the customer be right. The other option was: Friendship Between Political Opposites. The book launches October 1, 2020. The title correlates to a scene where I pass by a group of women at a campaign event for volunteers on election night, 2004. Presidential candidate John Kerry has conceded to George Bush, and one of the women asks the others: How can half the country be so stupid?

This is the wrong question, of course. Political ideology is not about intelligence. It’s about a myriad of factors, influences, and experiences that percolate in our brains and deliver us to either a Red or Blue altar. The real question is: How can we cooperate despite our preference for different approaches to our common problems?

Here’s a description of the book:

Julie Ethan and her husband, Larry, were religious conservatives raising five children and running a family business. Their closest friends and allies were a mixed-race couple with liberal political convictions. As a mini-memoir, Julie narrates this unlikely, yet exquisite friendship spanning more than three decades and several election cycles. As a guide, learn practical ways to depolarize and build bridges in your politically opposite relationships.

What's next for you as you continue on your path as a peacebuilder and changemaker?

One day, I’d like to be the President’s advisor on matters of communicating across the partisan divide. That’s the big hairy audacious goal. And while the current President could use my help, I’m also happy to help any of our congressional leaders to craft messages that strike the chord of our shared values and common desire for unity and peace. Why? Because dehumanizing the other side is not the answer. We must not fall victim to meta-perceptions that tell us the other side hates us so much they’d do anything to get rid of us. We all know how that story ends. Therefore, I recommend we get through this dark night of the soul as a nation with a mentality of relationships over politics, and we bring the elixir of cooperation into our shared future as we bind our wounds and repair what has been lost.

__

Want to follow in Julie's footsteps to build more peaceful and just societies? Explore the Kroc School's Master of Arts in Peace and Justice program.

Contact:

Justin Prugh

jprugh@sandiego.edu

(619) 260-7573

About the Author

The Joan B. Kroc School of Peace Studies (Kroc School) at the University of San Diego is the global hub for peacebuilding and social innovation. Founded in 2007, the Kroc School equips the next generation of innovative changemakers to shape more peaceful and just societies. We offer master's degrees in peace and justice, social innovation, humanitarian action, conflict management and resolution, and a dual degree in peace and law — programs that have attracted diverse and dynamic students from more than 50 countries. In addition to our graduate programs, the Kroc School is home to the Kroc Institute for Peace and Justice (Kroc IPJ). Founded in 2001, the Institute supports positive change beyond the classroom. Through groundbreaking research, experiential learning, and forward-thinking programs, the Kroc School and Kroc IPJ are shaping a future in which peaceful co-existence is the new normal.